Searching for MONDRAGONE (Italian/English)

Postcard, entitled: “The Identification of the Corps Recovered from the Church of S. Giuseppe from Ottajano”. Photograph by Crocco and Scarfoglio (MATTINO). Propriety of the Casa E. Regozino from Naples, Nr. III – Vesuvius’ Eruption Series – April 1906.

“Dopo la grande eruzione del 1872, tolti brevi periodi di riposo, il Vesuvio, fino al 1906 fu quasi sempre in attività […]. Ma poche volte la lava giunse fin nei boschi e nei campi coltivati […]. E mentre gli abitanti della regione occidentale più volte cominciarono lo sgombro delle masserizie, nella regione orientale, invece, specialmente in S. Giuseppe, il Vulcano presentava uno spettacolo piuttosto di divertimento che di terrore; nella piazza Garibaldi, nelle serate di estate, si vedevano capannelli di curiosi che contemplavano e ammiravano i graziosi getti del Vulcano, i quali divertivano allo stesso modo dello sparo di pedardi. Molte volte vi furono piogge di arene, di ceneri e di acque bollenti, che danneggiarono la raccolta delle uva; ma, essendosi perduta per fino la tradizione di queste, nessuno temeva altro pericolo oltre quello che incuteva la lava vulcanica” (segue in basso, dopo l’estratto della traduzione in inglese).

“After the great eruption in 1872, besides short periods of resting, mount Vesuvius had almost been active until 1906 […]. But just a few times, the lava could get to the woods and cultivated fields […]. And while the inhabitants of the northern region often began to rescue their proprieties, for the eastern region, especially in S. Giuseppe, the Volcano presented rather some kind of entertainment than terror. In the main-square Garibaldi, during the summer evenings, you could see bunches of curious people contemplating and admiring the Volcano’s graceful outflows, that amused in the same way as the shooting of fireworks. There had often been showers of sand, ashes and boiling waters, that damaged the grapes’ harvest; but, since even their cultivation had been forgotten, nobody was afraid of another danger beyond the volcanic lava’s demanding” (to be continued below, after the sequel of the original text).

Silvio Cola, “S. Giuseppe Vesuviano in History. Mount Vesuvius, and Its Eruptions. Historical Memories from Ottaviano, S. Gennarello, and Terzigno” [known as “TER[RA] IGNIS; i.e., Land of Fire; or, the Burned Ground”], 2nd Edition 1958 (1911).

“[N]el pomeriggio del giorno 7 [dell’Aprile 1906] S. Giuseppe ed Ottajano erano rimasti del tutto deserti, perchè la maggior parte dei cittadini, inconscii del pericolo che li minacciava, come a festa, si erano, nuovamente, recati suoi luoghi invasi dalla lava.

“Verso le ore 16, da qualcuno di S. Giuseppe si osservò la caduta di qualche lapillo della grandezza di un chicco di grana, tanto che dalla maggior parte della popolazione non vi si fece caso; ma, verso le ore 18 dello stesso giorno, la caduta dei lapilli divenne più rapida e più frequente e andò sempre più aumentando. Verso le ore 23 e 30 il Sindaco Ignazio Ambrosio, impensierito del pericolo sovrastante, fece telegrafare alla Prefettura di Napoli e, non avendo ottenuto risposta perchè si erano interrotte le comunicazioni, verso la mezzanotte fece telegrafare per mezzo della Ferrovia dello Stato. Mentre si telegrafava anche qui s’interruppero le comunicazioni” (segue in basso).

“In the afternoon of the 7th day of April 1906, S. Giuseppe and Ottajano were left completely deserted, because the great part of the citizens, unconscious of the danger that was threatening them, as for a party, had moved to the places invaded by the lava.

“Around 16 o’clock, somebody from S. Giuseppe observed the falling of some Lapillus of the size of a grain of corn, which the great part of the population, indeed, didn’t notice. But around 18 o’clock of the same day, the Lapillus’ falling fastened, and became more frequent, and was ever increasing. Around 23 and 30 o’clock the mayor Ignazio Ambrosio, preoccupied because of the impending danger, ordered to telegraph to Naples’ Prefecture; but since communications had been interrupted, around midnight he ordered telegraphing from the State’s Rail Station. While telegraphing was going on, communication was interrupted even there” (to be continued below).

“Towns that rise again at mount Vesuvius’ inclines”.

“Il Vulcano, intano, appariva tutto acceso, dando al Paese un colore rossastro; per l’aria si vedevano, continuamente, saette e lampi e si udivano muggiti e tuoni; i granelli avevano preso la grandezza di piselli e, battendo sui vetri delle finestre, davano l’idea di una pioggia di grandine” (segue in basso).

“The Volcano, in the mean-while, appeared all burning – giving a reddish colour to the town. In the air, you could see, again and again, arrows and flashes, and hear the roaring of thunders. The Lapillus had got the size of peas, and, while beating against the windows’ glasses, gave the idea of an hailstorm” (to be continued below).

Postcard, entitled: “A Building from Ottajano with its Glasses Broken by the Lapillus”. Propriety of the Casa E. Regozino, Gallery of Umberto, Naples, Nr. LXX – Vesuvius’ Eruption Series – April 1906.

“Molti cittadini, ingrossando la bufera, decisero di fuggire. Nelle vie si vide una folla immensa di popolo, che, tra pianti e singhiozzi, si allontanava, ed una turba di donne scapigliate, che imploravano la misericordia e la pietà Divina, mentre le campane suonavano a distesa.

“Dopo lo sprofondamento del Cono Centrale, il disastro si manifestò ancora più terribile: al grandissimo splendore, all’improvviso, subentrò una oscurità completa; la pioggia divenne meno intensa, ma le pietre aumentarono di grandezza tanto che una donna, colpita da una di esse abbastanza grande, stramazzò al suolo e, colpita da altre ancora, cessò di vivere. Con sul capo canestri, tavole, guanciali, coperte, sedie, si camminava senza saper dove, in ricerca di ricovero; molti ammalati o vecchi si ripararono in qualche pagliaio di campagna. Altri cittadini, per la maggior parte donne, avendo obbligato il Parroco ad aprire l’Oratorio dello Spirito Santo, vi si rifugiarono” (segue in basso).

“Many citizens, while the storm was increasing, decided to escape. On the roads you saw an immense crowd of people, that was removing under cries and sighs, and a flock of tousled women, who were imploring the Devine Charity; while the bells kept on chiming into the distance.

“After the collapsing of the Central Cone, the catastrophe manifested itself in an even more terrible way: the strong brightness was suddenly followed by complete obscurity. The rain decreased, but the stones became bigger – so that a woman, that was hit by a rather big one of these, felt to the ground, and, still hit by other ones, lost her life. With chests on the head, tables, cushions, carpets, chairs, you walked without knowing where to recover. Many sick or old people took refuge in some barn of the country-side. Other citizens, for the great part women, after having forced the Priest to open the Oratorium of the Holy Spirit, took refuge inside there” (to be continued below).

“Verso le sei a.m. del giorno 8, circa duecento persone si trovavano nell’Oratorio dello Spirito Santo; nessuno aveva preveduto che questo, per il grande peso dei materiali vulcanici, avrebbe potuto crollare; tutti quegli sventurati erano a sentire la messa del prete D. Salvatore Ferraro, quando un rumore terribile si udì e centinaia di grida strazianti echeggiarono per l’aere circostante. L’Oratorio era crollato, rimanendo in piedi la sola sagrestia” (segue in basso).

“Around 6 o’clock in the morning of the 8ht day, about 200 persons found themselves sheltered by the Oratorium of the Holy Spirit. Nobody had foreseen, that it could collapse, due to the great weight of the volcanic materials. All those unhappy-ones were listening to the mass held by Don Salvatore Ferraro; when a terrible noise was heard, and hundreds of dreadful cries echoed into the surrounding air. The Oratorium had collapsed; only the sacristy kept on standing” (to be continued below).

The Oratorium of the Holy Spirit of S. Giuseppe Vesuviano after the catastrophe.

QUI – LO STERMINIO DEL VESUVIO – NELLA NOTTE SENZA – ALBA DELL’ VIII APRILE MCMVI – ATTERRAVA – L’ORATORIO DELLO S. SANTO – E CUEI FEDELI – ACCORSI ALL’ALTO PERDONO – FURONO PIETOSA MACERIE // SIA QUESTA PIETRA – SACRA MEMORIA AI VENTURI // XXXI AGOSTO MCMXIII.

HERE – MOUNT VESUVIUS’ EXTERMINATION – DURING THE NIGHT WITHOUT – DAWN ON THE 8TH OF APRIL 1906 – TORE DOWN – THE ORATORIUM OF THE HOLY SPIRIT – AND THOSE DEVOTEES – FLED TO SUPREME REDEMPTION – WERE PITIFULLY DESTROYED // BE THIS STONE – SACRED MEMORY OF THE UNHAPPY-ONES // 31ST OF AUGUST 1913.

EX FLAMMIS ORIOR

FROM FLAMES I’M RISING

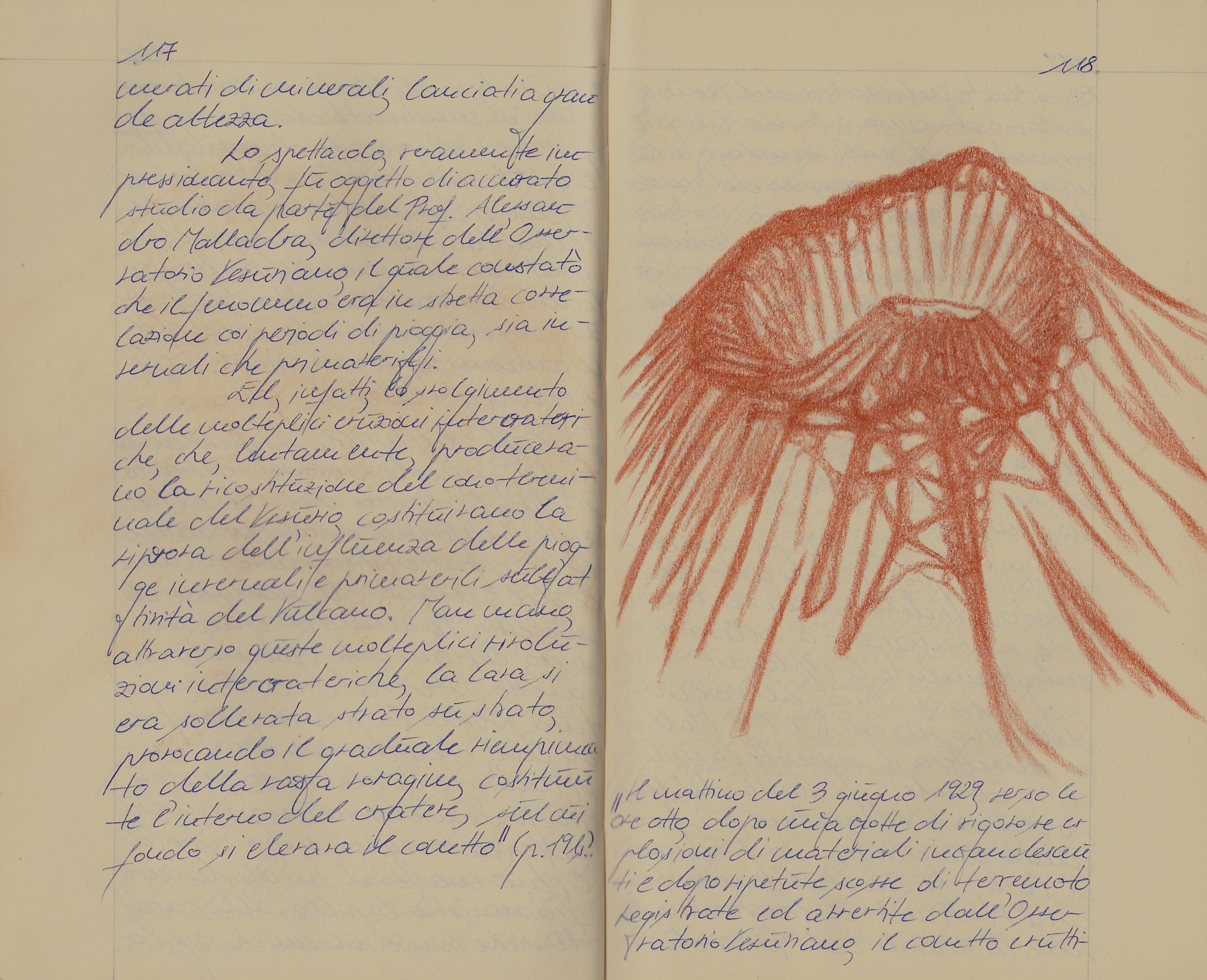

“A seguito del terribile sprofondamento del grande cratere, verificatosi dopo l’eruzione del 1906 e che aveva trasformato completamente la caratteristica parte terminale del Vulcano, col susseguirsi dei successivi fenomeni di eruzione, si era, lentamente, formato un conetto intercraterico, la cui frattura provocò la prima fuoruscita di lave, che riuscirono a contenersi nell’interno del vasto cratere, trasformandosi in una paurosa ciclopica voragine, entro cui ribollivano materiali incandescenti, frammisti a lapillo, alle caratteristiche bombe vulcaniche agglomerati di minerali, lanciati a grande altezza” (segue in basso).

“After the horrifying collapsing of the big volcanic crater, that was caused by the eruption of 1906 – and which had completely transformed the Volcano’s characteristical final part –, with the following ongoing phenomenons of eruption, slowly, there had formed a smaller cone inside the large crater itself. Its breaking provoked the first emission of lava, that succeeded in being contained inside the vast crater itself that, by the way, was transformed into a threatening vortex, in which burning materials bubbled, mixed up with Lapillus, with the characteristical volcanic bombs consistent of minerals, thrown up to great altitudes” (to be continued below).

“[L]o svolgimento delle molteplici eruzioni intercrateriche, che, lentamente, producevano la ricostituzione del cono terminale del Vesuvio, costituivano la riprova dell’influenza delle piogge invernali e primaverili sull’attività del Vulcano. Man mano, attraverso queste molteplici rivoluzioni intercrateriche, la lava si era sollevata strato su strato, provocando il graduale riempimento della vasta voragine, costituente l’interno del cratere, sul cui fondo si elevava il conetto.

“Il mattino del 3 giugno 1929, verso le ore otto, dopo una notte di rigorose esplosioni di materiali incandescenti e dopo ripetute scosse di terremoto registrate […] dall’Osservatorio Vesuviano, il conetto eruttivo, situato nel cratere del Vesuvio, si staccò da cima a fondo lungo il versante nord, inabissandosi in buona parte nella voragine del condotto eruttivo. Dallo squarciò scaturì, zampillando, una copiosa fiumana di lava, che in due ore invase tutto il quadrante nord-orientale del cratere, raggiungendo l’orlo più basso del cratere stesso. Verso mezzogiorno le lave fluenti cominciarono a precipitare nella valle dell’inferno con diverse cascate […]. Nello stesso tempo, dal conetto eruttivo, profondamente decapitato e ridotto ad un rudere turrito, continuarono a sollevarsi energicamente le esplosioni” (segue in basso).

“The proceeding of multiple eruptions inside the crater itself that, slowly, produced the reconstitution of the Volcano’s final cone, proved the influence of winter’s and spring’s showers on the Volcano’s activity. By and by, due to these multiple revolutions inside the crater itself, the lava had grown by layers on layers – so provoking the gradual replenishment of the large vortex, that constituted the crater’s interior, at whose bottom the smaller cone was rising.

“In the morning on the 3d of June 1929, around 8 o’clock, after a night of vigorous explosions of burning materials, and after the perpetuation of earthquakes that had been registered by the Vesuviano’s Observatory, the little erupting cone, that was situated inside mount Vesuvius’ crater, broke from top to ground alongside the northern slope, while, to a great part, precipitating into the vortex of the eruptions’ conduit. From the cleft a big flood of lava poured out, that in two hours had completely invaded the crater’s north-eastern quadrant, while reaching the lowest edge of the crater there. Around noon, the lava began to precipitate into the Valley of Hell in the shape of different cataracts. In the mean-while, from the little erupting cone, that had been profoundly decapitated and reduced to the shape of a turret’s rovine, the explosions continued to be elevated energetically” (to be continued below).

“Terzigno era minacciata, correva serio pericolo, il mostro lavico avanzava su di esso.

“Nelle chiese si pregava e senza tregua si facevano processioni di penitenza. Ma ciò a nulla valeva. La corrente lavica non si fermava.

“Erano le nove antimeridiane di martedì cinque giugno, quando si pensò a S. Antonio. Alcuni popolani, presa la statua dalla vicina chiesetta, […] a braccia la trasportavano sul fronte lavico. Quivi l’affidarono ad alcuni soldati, i quali la retrocedevano a misura che il mostro lavico avanzava” (segue in basso).

“Terzigno was threatened. It took serious danger. The lava-monster approached it. People kept on praying in the churches and, without hesitation, made processions of redemption. But it didn’t help. The lava’s torrent didn’t stop.

“It was at 9 o’clock in the morning of Tuesday on the 5th of June, when they remembered S. Antonio. A few people, after they had taken the statue from the nearby church, carried it to the lava’s front in their arms. There, they gave it to some soldiers, who retreated together with the statue, as the lava-monster was approaching them” (to be continued below).

“Trascorse così l’intera giornata del 5 giugno, allorchè, verso le ore 23, il mostro lavico, improvvisamente, accentuò il suo corso tanto che i soldati, impauritisi, fuggirono, lasciando sola la statua di S. Antonio. Senonchè, immediatamente dopo, tutto ad un tratto, il mostro stesso si fermò dinnanzi alla statua, dividendosi in due rami, e, proseguendo così fino alle ore 16:30 del giorno successivo, lasciò incolume non solo l’Immagine sacra, ma anche la chiesetta, che era stata circondata dalla lava com in un ferro di cavallo. Si gridò al miracolo!” (segue in basso).

“So proceeded the whole day on the 5th of June; when, around 23 o’clock, the lava-monster suddenly accentuated its conduit. The soldiers, being frightened, flew, and let S. Antonio’s statue behind, and alone. But immediately afterwards, the monster stopped right in front of the statue, while dividing itself into two branches, and, proceeding like that until 16 and 30 o’clock of the following day, let undamaged not only the holy Image, but even the little church, that had been surrounded by the lava like in a horseshoe. The miracle was announced!” (to be continued below).

Terzigno – S. Antonio from Padova amidst the soldiers and people, a few metres distant from the lava.

“Più tardi, poco dopo le ore 17, […] si recò sul fronte lavico anche Sua Eminenza il Cardinale Alessio Ascalesi, il quale, dopo essersi raccolto per qualche istante in fervida preghiera, più volte levò in alto la Croce ed impartì la benedizione, implorando dal Signore la fine del flagello. [–] Da verifiche, eseguite dalle Autorità, risultò che i danni, prodotti da quella eruzione, erano stati i seguenti: 178 vani utili distrutti dalla corrente lavica, […] 50 vigneti completamente rasi al suolo, buona parte dei boschi demaniali e della Principessa dei Medici incendiati; complessivamente, circa quattrocento persone senza tetto e danni per oltre un milione di lire” (segue in basso).

“Later on, shortly after 17 o’clock, His Eminency the Cardinal Alessio Ascalesi, also adjourned to the lava’s front. After having gathered himself for a few instants in fervent prayer, more than one time he raised the Cross, and gave his benediction, while imploring the Lord that the scourge may end. – From verifications conducted by the Authorities, the damages produced by this eruption, were the following: 178 useful spaces destroyed by the lava’s torrent, 50 vineyards completely burned to the ground, a good part of the State’s Propriety Woods, and the Woods of the Medici’s Princess, set on fire. Altogether: around 400 people without shelter, and damages for over a Million of Lire” (to be continued below).

Appendix

“Come, attraverso i secoli, S. Giuseppe Vesuviano, dopo l’azione distruttrice del Vesuvio, risorse sempre, così è risorta anche dopo le distruzioni, causatele dall’ultima guerra, grazie allo spirito di iniziativa, alla tenacia, alla solerzia ed alla intensa attività dei suoi abitanti”.

“Like, over centuries, S. Giuseppe Vesuviano, after mount Vesuvius’ destructive action, has always been rising again, so it has also been rising after the destructions caused to it by the last war, – thanks to the spirit of initiative, the tenacity, the alacrity, and the intense activity of its inhabitants”.